In my last post about the history of return-oriented programming I showed that we are not dealing with a completely new technology when we are talking about return-oriented programming. However, the technology is evolving to a point where even the world of academia thinks it worth discussing it in theoretical conferences. Until recently return-oriented programming has always been platform dependent so that one specific implementation was only able to work on one single platform. To sharpen the point a little further current approaches only target one specific compiler for one platform in general. Even though this is not necessarily the case for variable length instruction sets like the IA-32/64 instruction set, where the search for instruction sequences can be performed without paying attention to the alignment restrictions, for all platforms where alignment is enforced the current approaches are still very limited.

In this post I will start showing a set of algorithms which can be used platform independently to locate suitable instruction sequences for return-oriented programming.

So let’s get started with defining return-oriented programming to get an idea where we are eventually trying to end up with.

The goal is to build a program from existing code chunks of another program or commonly used libraries. A program built from the parts of another binary is called a return-oriented program. The individual parts that form a return-oriented program are named gadgets. A gadget is a sequence of instructions in the target binary that provides a usable operation, such as addition of two registers. To be able to build a program from gadgets, they must be combinable. Gadgets are combinable if they end in an instruction that changes control flow in a way that can be controlled by the attacker. Instructions at the end of gadgets are named free-branch instructions. A free-branch instruction must satisfy the following properties:

- The control flow must change at this instruction.

- The target of the control flow must be controllable (free) such that the input from an attacker controled register or memory offset defines the target.

After this small definition of what we are actually looking for we can now move on and discuss the algorithms which we will use to help us find instruction sequences which satisfy the above definition.

As we need a starting point for our search of useful instruction sequences, the first step is to locate all free-branch instructions in the targeted binary (In BinNavi this is a single SQL query). After we have collected all of the free-branch instructions we start with phase one of our algorithms, data collection within the binary. The goal of the data collection phase is to provide us with the following information:

- What possible paths are usable for gadgets and end in a free-branch instruction.

- What does the REIL representation of the instructions on the possible paths look like.

If you are not familiar with REILs ([R]everse [E]ngineering [I]ntermediate [L]anguage) concepts be sure to check our article we have posted a while back to get you started.

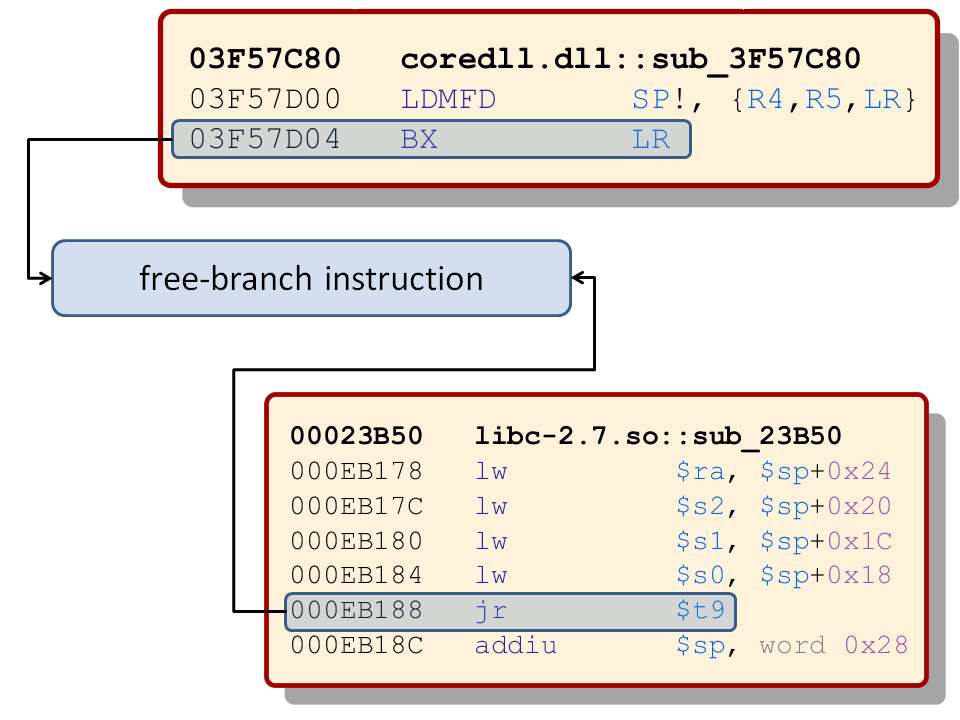

Now that we have a goal definition for our first phase algorithms we can start looking into the algorithms to get the desired data. To find all paths which could provide useful instruction sequences for gadgets we use an algorithm which traverses backwards through the control flow graph of all the functions where we found free-branch instructions. Using the free-branch instruction as our starting point we walk upwards instruction by instruction until no more instructions are contained in the initial basic block. The following graphic shows examples for ARM and MIPS free-branch instructions.

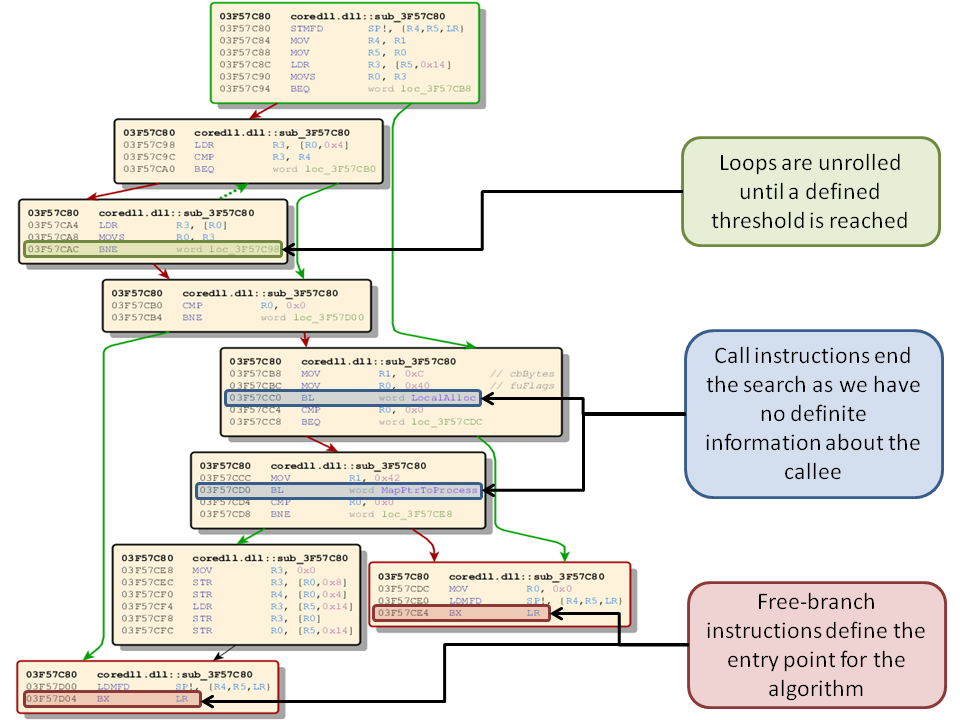

If a basic block end is reached we collect all predecessor basic blocks for our current basic block and traverse them like we have traversed the initial basic block. Given an arbitrary selected function we can now see how many possible paths we can find using this function.

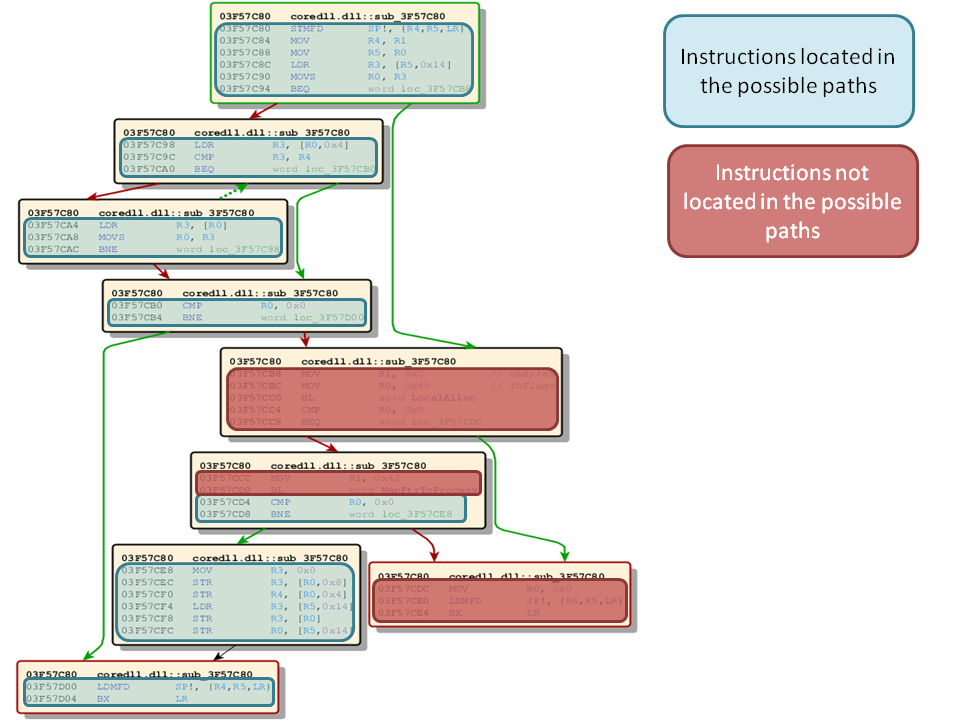

As our selected function has multiple entry points for searching we are traversing though the graph twice, once for each free-branch instruction. Lets take a closer look at what the path algorithm will find given we look at only one free-branch instruction with a defined maximum instruction threshold of 15 instructions. A threshold is necessary because otherwise it will get infeasible to analyze all effects of encountered instructions. To get an impression what instructions are reachable and what instructions are not lets take a look at our function with all reachable instructions highlighted. Remember we are only looking at one of the free-branch instructions.

So how many possible paths for useful instruction sequences are we looking at? A path has no minimum length and we are storing a path each time we encounter a new instruction. In total this specific free-branch instruction will result in 47 possible paths for gadgets. This number now appears to come out of nowhere but if you think about it [Depth-limited search (DLS)] and take a closer look at the graph you will come up with the same number of paths.

As we have seen, searching for paths is really easy and provides us with information we need later to build our gadgets. As a side note, not only all instructions in a sequence but also all traversed basic blocks must be stored for a path to be able to differentiate between them correctly.

What we now have is all possible paths which are terminated by our selected free-branch instruction. So lets move on and take a closer look at instructions which are located on these paths. What we are aiming at is a representation of an instruction fulfills all of these requirements:

- It must be platform independent.

- It should be easy to compare it to other instructions in this representation.

- It should be easy to combine multiple instructions.

- It should be easy to work with.

Platform independence is important to us, because we are lazy and only want to rework parts which we can not represent in a platform independent manner. Therefore we are aiming at a representation which allows us to specify all core parts once and use them for all platforms we care about. This is the reason to use a REIL representation for all instructions we want to use in our gadgets. REIL provides us with a unified layer on which we can base all algorithms working with the extracted information. We want to be able to compare two instances of this representation easily therefore we choose to use expression trees as our representation. But what are expression trees and how do they solve points 3 and 4 of our requirement list.

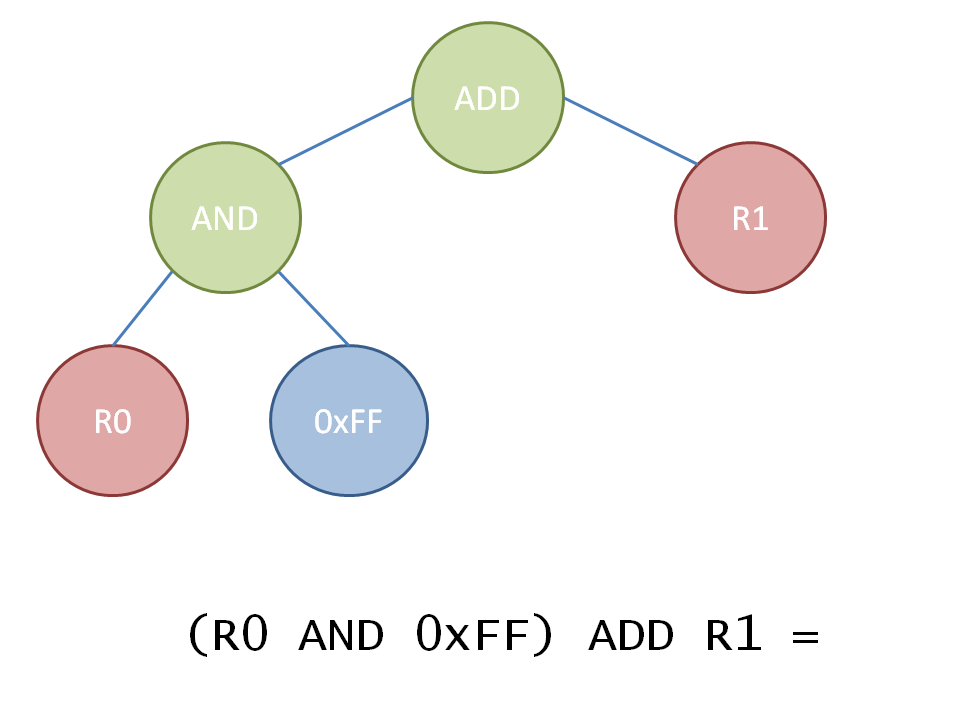

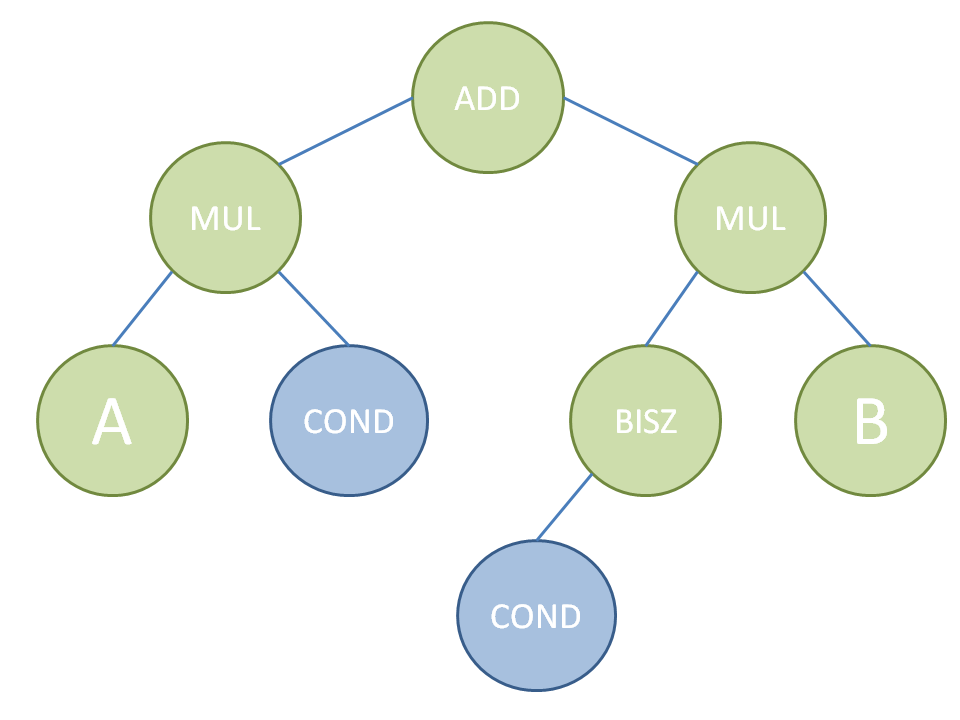

Expression trees are a simple structure which is can be used to build arbitrarily complex functions in a binary tree form. An expression tree is build from nodes which can either be leaf nodes, meaning they do not have any nodes below them, or non-leaf nodes which have one or two child nodes. In case of an expression tree leaf node, nodes are always operands and non-leaf nodes are always operators. To give you an idea how an expression tree looks like and what we can use it for I have taken a simple equation and put it into expression tree from.

So how do expression trees based on REIL help us with our defined requirements and how do they relate to return-oriented programming? Using REIL we have a platform independent representation of an instructions formula. Using a tree structure we can compare two trees and sub-trees of them easily. Multiple instructions can be combined easily because operands are always leaf nodes and therefore an already existing tree for an instruction can be updated with new information about source operands by simply replacing a leaf node with an associated source operands tree. Therefore we have found a solution to fulfill all of our requirements.

Now we need to collect all information about instructions which will be used on paths earlier extracted. We do this by using the same algorithm as before with a minor difference. In pathfinding it is important to treat encountered instructions as new even though we might have seen them in our path already (think loops). Collecting all possible instructions and generating an expression tree representation for them does not need to treat already encountered instructions as new because their expression tree representation will not change. When the algorithm is finished we have a REIL expression tree representation for each instruction which we have encountered on any possible path leading to the free-branch instruction. As some instructions will alter more than one register one tree represents the effects on only one register and a single instruction therefore might have more than one tree associated with it.

Notice that until now we have not discussed any memory related issues and also have not mentioned any specialties which we could encounter for example conditional execution of an instruction. Lets start with memory related content and how we can address it.

For memory reads even if multiple memory addresses are read we do not need any special treatment. This is because memory is either read from a constant or from a register. Both have a defined state at the time the instruction is executed and can therefore safely be used as source.

Memory writes are different because they can use a register or a register + offset as target for storing memory. This register holding the memory address can be reused by instructions which follow the current instruction. Therefore it can not safely be used as target because information about it could get lost. We deal with this problem by assigning a new unique value every time a memory store takes place as key. Therefore we do not lose any information about memory writes.

We still need the information about where memory gets written. We can do this by storing the target register with a possible offset in our expression tree as a node. Doing this prevents sequential instructions from overwriting the contents of the register. To make this a little clearer take a look at the following graphic.

What this expression tree stores is that memory referenced by register R1 will be written with the contents of register R0 + 40. Notice that generally for both sides of the expression tree memory load statements are also valid therefore allowing direct memory to memory transfers.

We have now covered all but one last issue remaining before all instructions can be displayed in an expression tree. Instructions which perform different operations depending on current system state. System state is in this case for example a flag condition for platforms where flags exist.

What we are looking for is a way to only have a single expression tree for a conditional instruction. Therefore we enhance our expression tree for such instructions with some simple math to make sure evaluating it always yields a correct result.

What does this do? If condition COND is true (in this case true is equal to one and false to zero) the left side’s multiplication result is A and the right side’s multiplication result with !COND is zero. Using this canceling mechanism we are able to avoid to store multiple trees for conditional instructions.

To wrap up what we have seen in this post is the data collection phase of our algorithms for platform independent return oriented programming. We have worked with BinNavi and REIL to get a platform independent representation of paths and instructions which we can later use to build our gadgets. This is basically ground work which is essential for our purpose. In the next post we will work with the extracted data and start to merge it into an instruction sequence representation. For all the readers which have stayed with me until the very end thanks for your attention 🙂

Can’t wait for the next post!

cool writeup, Tim. Rock on!

You probably mean “non-leaf nodes are always _operators_”. Thanks for your great article!

yep you are totally right thanks 🙂 Fixing it now.

Full Statement

Algorithms for platform independent return-oriented programming (I of III) | blog.zynamics.com